Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images; Al Drago-Pool/Getty Images

- The Federal Reserve's plan to let inflation run hot could shake up decades-long regimes in markets and the economy.

- Higher inflation stands to lift cyclical assets and slam Treasurys and high-grade corporate bonds.

- A period of steadily high inflation and strong growth could replace the past decade's weak expansion.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

Regime changes are usually identified years after they first emerge.

LeBron James' decision to take his talents to South Beach kicked off a new era of NBA "superteams," assembled by friendly superstars coordinating their movements via free agency. Robert Downey, Jr.'s portrayal of Tony Stark, aka Iron Man, in 2008 set the stage for a new box-office (and now streaming) behemoth. And like it or not, Mark Zuckerberg's invention of Facebook brought a paradigm shift to online privacy and socialization.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell may be next up. Investors have been bracing for inflation in the still-nascent Biden era. But how the Fed guides the economy forward will decide whether markets are in the midst of their own regime change or if investors can reuse their pre-pandemic playbooks. It's looking for the moment like it could be the start of a new era in markets.

The central bank rolled out a new policy framework in August that targets inflation temporarily above 2% and maximum employment. Powell's comments since then signal the Fed's extremely easy monetary policy will stay in place well after the economy reopens.

The guidance, while vague, marks a stark shift from the recovery following the global financial crisis. The initial bounce out of the Great Recession quickly gave way to secular stagnation, a phase coined by famous economist Larry Summers to describe a period of weak growth and low inflation.

The Fed's new strategy aims to learn from the last recovery and run the economy hot, bucking the decades-long precedent that explicitly links price growth with hiring.

"There was a time when there was a tight connection between unemployment and inflation. That time is long gone," Powell said in a Wednesday press conference. "We had low unemployment in 2018 and 2019 and the beginning of '20 without having troubling inflation at all."

Laying a foundation for the next decade of gains

Recession recoveries have similar market dynamics in their early stages. Investors dump defensive assets like Treasurys and growth stocks and move their cash into riskier vehicles in hopes that stronger economic growth will lift their value.

Those trades have largely played out. Treasury yields surged to their highest levels in more than a year as investors positioned for stronger inflation. Tech stocks tumbled through February, and sectors that lagged through the pandemic outperformed.

Recent weeks have been frothier. Tech sell-offs have been followed by dip-buying as traders moved their focus from inflation concerns to reopening optimism and back again. The 10-year yield continues to climb, but at a slower pace than seen earlier in March. Markets are seemingly at a crossroads, waiting to see just how strong the recovery ends up being.

"We're in the early stages of a regime change, where maybe the easy money has been made," Rich Steinberg, chief market strategist at The Colony Group, told Insider. "I would love to tell you there is a playbook you could follow that's going to give you the secret sauce for how to be directionally correct throughout this move. I don't think that secret sauce exists."

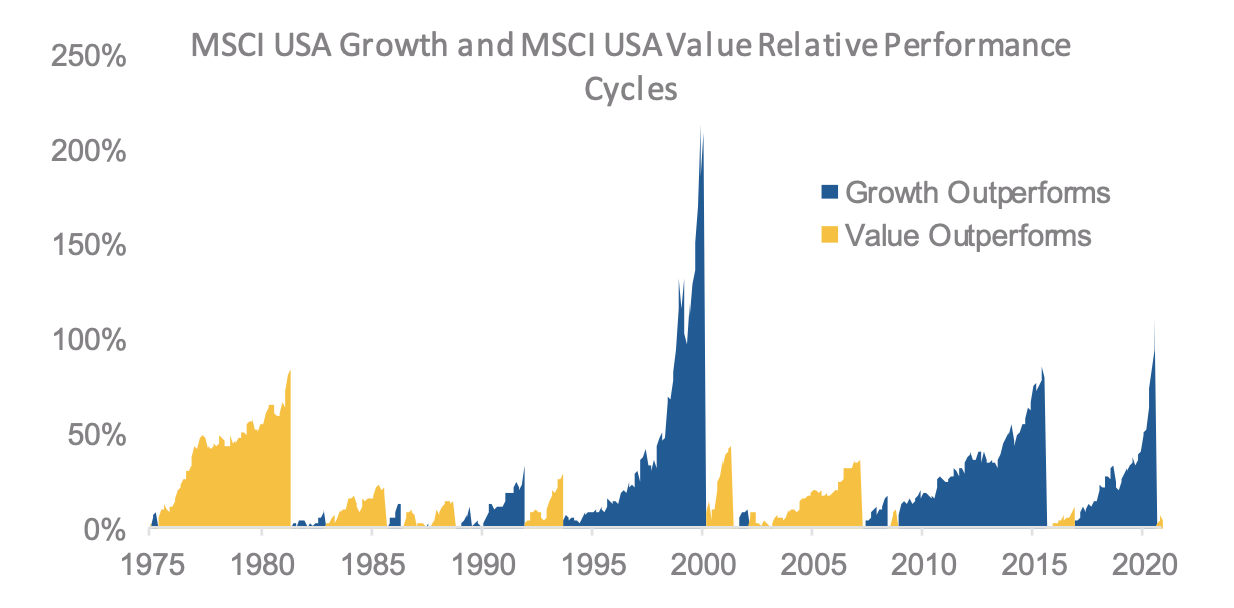

The Colony Group

To be sure, the change in market leadership has a way to go before reversing nearly a decade of growth dominance. Barring a short stint in 2015, such stocks handily outperformed their value counterparts after the financial crisis as the low-growth-low-inflation backdrop boosted their appeal.

Aggressive fiscal stimulus and the Fed maintaining easy monetary policy stand to change that. The combination can supercharge economic growth and inflation to levels unseen through the late 2000s and 2010s, Jason Draho, head of asset allocation in the Americas at UBS, said in a note.

Democrats' plan to pass a massive infrastructure plan should provide an even bigger boost to cyclical assets, as well as lift long-term productivity and economic growth, he added.

If value stocks and recently unloved sectors become the market's new winners, the growth giants and Treasurys that thrived for more than a decade are likely to lose. Growth stocks' valuations are closely tied to interest rates, since investors project out the company's long-term expansion and use rates as a discounting tool. Higher rates cut into such firms' future profits and, in turn, their stock valuation.

Higher inflation is also the "enemy of fixed income" and will likely drag on Treasurys, mortgages, and investment-grade corporate debt, Todd Jablonski, chief investment officer of Principal Global Asset Allocation, said.

"At the current level of low rates, what you're looking at in fixed income is a very expensive proposition for stability, and not as much income as one might like," he added.

YouTube / 20th Century FOX

A whole new world, or business as usual?

It remains too early to tell whether the economy is entering a new expansionary cycle or starting the kind of regime change that only comes once every few decades, Jablonski told Insider.

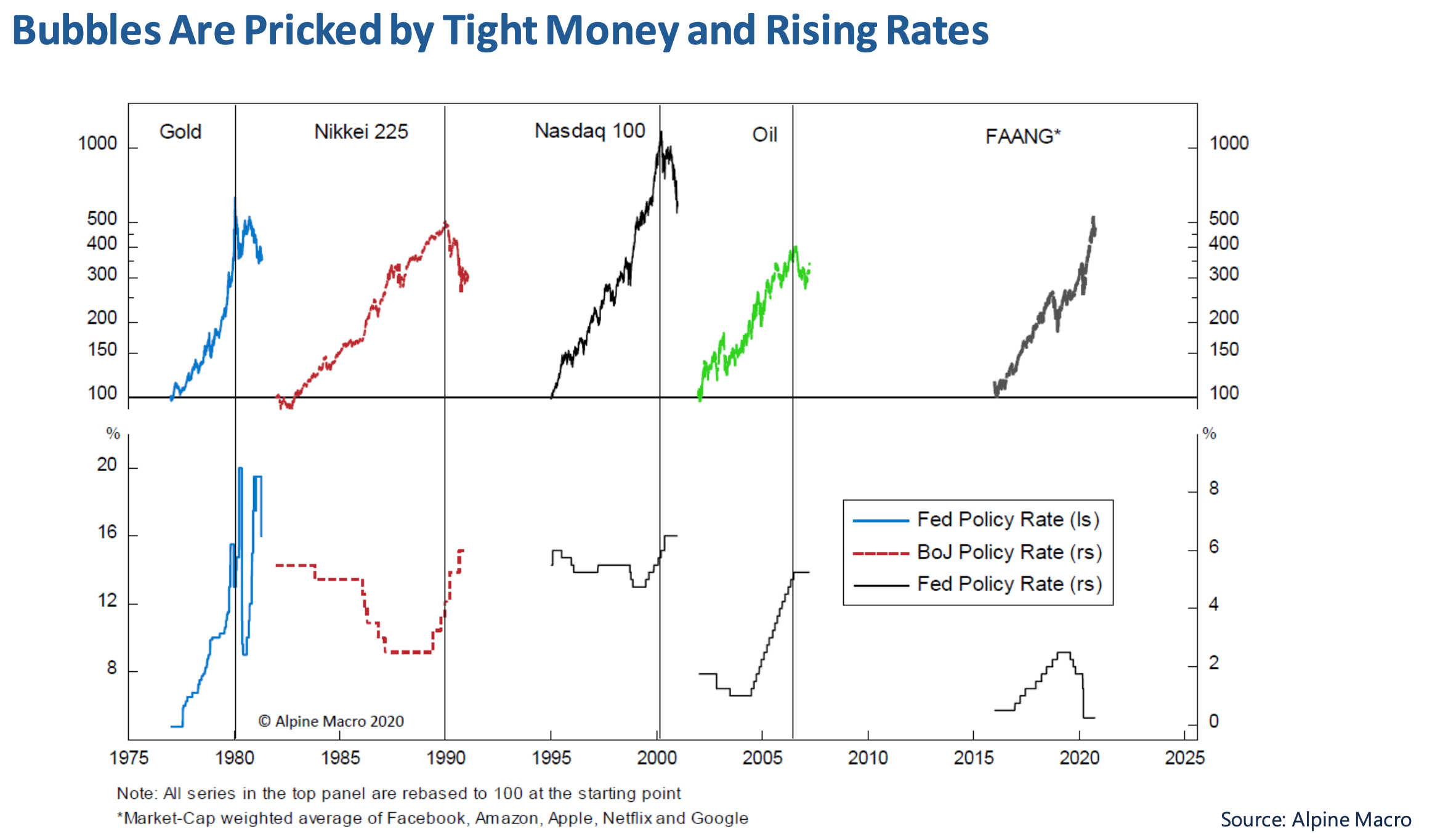

The last major regime change was arguably the dot-com boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s. The advent of the internet and a new wave of technology companies kickstarted the tech sector dominance seen up until today.

Looking even further back, the "Great Inflation" that dominated the 1970s and ended with former Fed Chair Paul Volker's unprecedented rate hikes marked another momentous change. Retaliation to the high-rate environment materialized in the 1980s with new mindsets: profit rules all, trickle-down economics, and, as made famous by fictional financier Gordon Gekko, the philosophy that "greed is good."

The kind of regime that materializes after the pandemic depends on just how much inflation the Fed is comfortable permitting, Jablonski said. The CIO said he expects price growth to crest at 3% during the recovery, but that surge is expected to quickly fade soon after.

If there's enough momentum to drive "real, organic, privately led inflation" after that peak, the country may finally buck the low-growth-low-inflation era, Jablonski said.

"The question becomes, after this cresting ... where do we settle? Do we settle at 2.5%, or do we settle at 2%? There's an enormous difference between those numbers!" he added.

The market's reaction won't come overnight. Asset classes that thrived in past regimes only started to decline well after relevant central banks lifted rates multiple times. The Fed's latest projections suggest its first post-pandemic rate hike won't arrive until after 2023, leaving plenty of time for the market to swing between regime-change positioning and a return to past year's norms.

The Colony Group

Trying to time a regime shift and a bursting of the related bubble "is extremely difficult and can be extremely painful if you're on the wrong side of the trade," Colony Group's Steinberg said.

While the change's timing is cloudy, it's growing more likely that the market is on the brink of a seismic shift, Draho said. Continued support from the Biden administration and the Fed could replace the lower-for-longer regime seen over the past decade with a push to run the economy hot.

"What seemed improbable six months ago is becoming increasingly plausible and investors need to be prepared," Draho added.

The key, for now, is composure. The Fed has said it will "be patient" in waiting for inflation to crest and then settle at an elevated level before pulling back its historic monetary support. Investors might be tired of the central bank's ambiguity, but the balance between overheating the economy and repeating a phase of secular stagnation is a difficult one to strike.

"The Fed is the snail on the edge of a razor. And they're trying to be careful to live, to get through it, but also not to move too fast and get cut," Steinberg said.